How to conduct a Proper Financial Audit?

What Is a Financial Audit?

A financial audit is the investigation of your business’ financial statements and accompanying documentation and processes, and is performed by someone who is independent of your organization. These often-annual events probe your company’s financial position: They look at your accounting records, internal control policies, and accounts in accordance with industry-accepted accounting standards. This process can look and feel as if someone is scrutinizing your sensitive files, searching for errors and misstatements. However, financial auditors use this process to assure your stakeholders (and any interested outsiders) of your company’s financial position. They give them reasonable assurance — not absolute assurance — and they give your company’s financial documentation more value. Other reasons to conduct an audit include to verify that you are in compliance with regulatory agencies, and to protect your company from the risk of fraudulent financial practices.

Independent financial auditors are people who are not on the payroll of your company and do not have a stake in your outcome. At the conclusion of an audit, they render their opinion on the integrity of your documentation. Financial auditors can perform an external or an internal audit for you, but they must not have a stake in your company.

While external audits assess financial risks and statements, internal audits go further and consider your business’ growth, impact to the environment, employee culture, and reputation. Internal auditors report to your board and senior management within your governance structure and, instead of just providing reasonable assurance to your stakeholders and outsiders, they offer ways to improve your company overall. Performing regular internal audits also shows the external auditors that your company has a means to improve your internal controls and thereby manage your organization effectively.

There are many different types of checklists available for financial audits. Whether you are an auditor, or you own a company and want to prepare for an audit, you can use a checklist to get ready. With membership to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), you’ll receive auditing checklists for everything from basic auditing to assessment of the risk of fraud. The United States Government Accountability Office (US GAO) also puts out checklists for federal auditing. Additionally, there are self-assessment checklists you can review prior to your audit, whether your business is public, private, or nonprofit.

What Is an Integrated Audit?

An integrated audit is one that combines the financial statement audit with an audit of your internal controls. In 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act. This Act required strict reforms by corporations to prevent accounting fraud. The act had substantial impact on the industry: Under it, senior management became responsible for certifying the accuracy of their financial statements as well as for instituting internal controls and reporting on those controls. This crackdown on corporate fraud also led to the creation of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), which provides guidance for integrated audits. Separately, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) provides enforcement. The SOX Act also mandated that public companies undergo integrated audits. Furthermore, auditing professionals say that an integrated audit is incomplete unless it also reviews the company’s Information Systems (IS) processes. IS, financial, and operational controls are mutually dependent on each other in order to foster an environment of support and efficacy.

The PCAOB guide on performing integrated audits includes the following requirements:

Audit Planning: In addition to the requirements laid out in the PCAOB’s Auditing Standard (AS) 2201.09, the auditor must plan a risk assessment. This risk assessment should focus on possible weaknesses in your company’s internal controls that can affect financial reporting.

Entity-Level Controls: Entity refers to your whole company. Entity-level controls refer to the processes that help ensure that you carry out your company-wide management directives effectively. Your auditor will examine these entity-level controls, and this examination determines the amount of testing they will have to do on other controls. If you have very strong, monitored control activities that your management is unable to override, your auditor may decrease controls testing in other areas.

Top-Down Approach: Auditors audit in a specific order, going from a review of overall risks to the controls over financial reporting. Then, they go to entity-level controls and on to significant accounts and disclosures. This process is top-down because it begins with the highest-level picture in order to determine the controls to test.

Controls Testing: During an integrated audit, your auditor tests the design of your controls as well as their operational effectiveness. This testing is where your auditors spend the majority of their time while they are auditing your business.

Reporting: Your auditor will form an opinion on whether your internal controls over your financial reporting are effective. According to the Auditing Standards requirement, the report wording must be highly specific. These reports must also be uniform, regardless of the individual needs of each audit.

The SOX Act requires integrated audits of larger, publicly held companies. The Act does not require smaller public or private companies to have an integrated audit — in general, these institutions only need audits of their financial statements. A small public company or a private company may want to have an integrated audit performed when they are preparing for sale. The auditor’s verification of a strong system of controls can improve the sales price of the company.

Outside of integrated audits, audit types focus on single processes. We have already discussed information systems auditing; other unique audits include operational and compliance audits. Operational audits focus specifically on the business processes. Some of these processes affect the finances, and some do not. An internal audit should address these operational processes as well as the accounting procedures that affect them and are affected by them. Your auditors should be able to identify implementation issues and recommend remedial actions for improvement. Compliance audits deal specifically with the level of compliance with internal policies or external regulatory requirements.

What Is the Purpose of an Audit?

Your auditor aims to give you an objective appraisal of your company’s financial situation based upon its documentation. An audit also provides proof that your documents accurately represent your situation (your auditor’s final report serves as this proof). Moreover, your auditor is there to improve your processes by providing suggestions and pointing out any inconsistencies.

The Big Four, the largest professional services networks in the world, specialize in auditing globally. Although these are certainly not the only firms that you may retain to perform your audit, they possess longstanding esteem in the finance profession. Together, these four professional service networks currently account for the majority of public-company audits as well as for those of a large number of private firms. The Big Four are KPMG, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Ernst & Young. They are networks (and not discrete firms) because of the way they are structured: They are independently owned and operated, but each functions under the umbrella of their respective “parent” firm. Under this parent firm, each of these networks shares branding, name, and quality standards for their services. These services include auditing, assurance, tax law, consultation, actuarial services, legal services, and corporate financial advice.

With documentation dating from 1314, England boasts the earliest recorded financial audit. In the United States, the Industrial Revolution forced the widespread adoption of financial auditing. The railroad industry, in an effort to control costs and operating ratios, became an auditing pioneer. After the 1929 stock market crash, auditing became obligatory for companies that wanted to participate in the stock market. Investors came to rely on the financial reports that auditors produced as a part of an overall audit. In 1934, Congress commissioned the SEC as the regulatory agency for auditing requirements and standards.

Why Is Auditing Necessary?

Financial auditing was not only necessary for the oversight of companies traded on the stock market, but was also used as a mechanism for fraud detection and finance accountability. However, in those early days of the SEC, company managers produced audit reports. Independent auditors did not conduct the audits. Companies implemented significant changes in auditing procedures only after intensely adverse business events occurred. For example, physical inspection of inventory became mandatory only after the treasurer of McKesson & Robbins (a pharmaceutical concern) discovered that the company was a front for an illegal bootlegging operation. This scandal also precipitated another mandate: The SEC now required public companies to appoint external audit committees.

Experts in the financial industry say that the future of auditing will bring even more regulatory control in order to stay consistent with the traditional requirement. Given the last few years of potent technological advancement, especially in the realm of automation and outsourcing, the trend toward more regulatory control is significant. Experts cite the possible need for changes to audit timing and frequency. They also say that auditors may need more education on technology and analytical methods. If this proves to be the case, cross-discipline auditing may become necessary. Sampling may become obsolete as auditors become able and necessary to complete full audits. And, the industry may have to revisit the concepts of materiality and independence. Materiality assigns a cut-off point to transactions it considers insignificant. Independence concerns the question of the auditor’s independence (i.e., whether or not they have a financial interest in the business they are auditing).

You need an audit if you are a publicly held company or see a public offering in your future. You will need auditing documentation for the year that your company has its initial public offering (IPO) as well as for all subsequent years. If you accept funding from the federal or state government, you may need an audit. Some banks will also require an audit if they give you a particularly large loan or if they consider you high risk. Finally, you may want an audit because it can mean the difference between being approved or rejected for a loan and getting a low or high interest rate.

How Is an Audit Done?

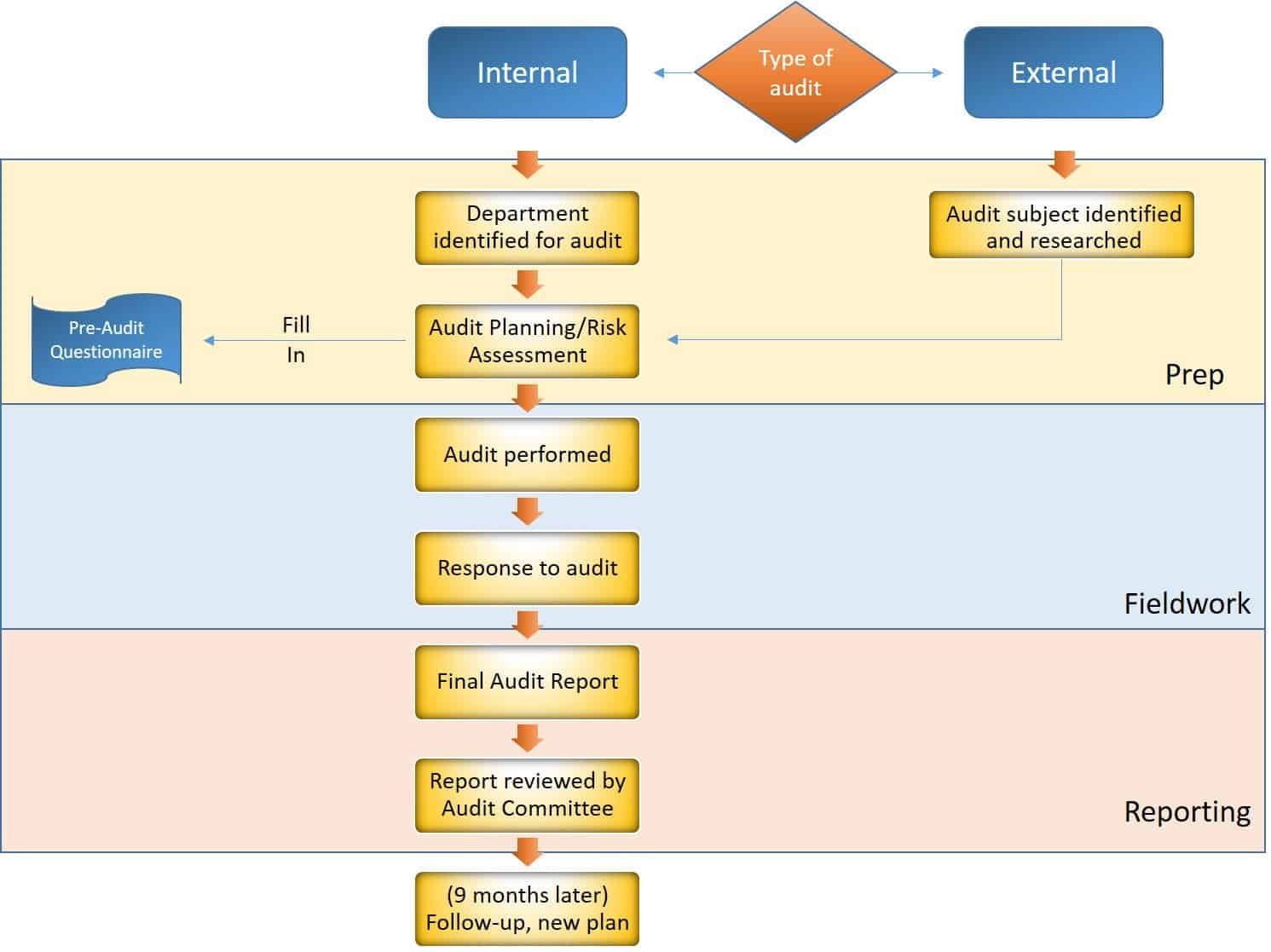

You can break down audits into three main phases: prep, fieldwork, and reporting. Each phase can be further broken down as well. For the prep work phase, there are eight main steps:

Receipt of Assignment: This step tells your auditor if they have to perform an audit of your financial statements or if they must complete a more comprehensive performance audit or compliance audit. They may begin with a very vague assignment, but as auditing experts, they will be able to quickly identify the job’s pertinent objectives.

Research the Audit Subject: The AICPA puts out Statements on Auditing Standards (SAS). These publications give guidance to external auditors. The U.S. GAO also releases their Yellow Book, which are standards for auditing government agencies. Both types of publications are specific about the questions auditors should ask their subjects prior to conducting the risk assessment. These include understanding such things as the industry, the regulations, the nature of the entity, the entity’s objectives and strategies, the method the entity employs to measure and review financial performance, and the entity’s internal controls. If possible, many auditors stick to the same as last year (SALY) philosophy to save time during this phase. This means that they perform the audit in an identical manner as the previous year. However, many auditors do not agree with this approach because they feel that it’s lazy.

Determine Audit Criteria: This is the benchmark for the audit. Auditors conduct financial audits and check them against the Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS), published by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). For audits that go beyond the finances, the client and auditor must agree on the benchmark prior to the audit.

Perform the Risk Assessment: There are two parts to a risk assessment: breaking the audit into chunks and assessing the risk of each chunk. The SASs already break up financial statement audits into pieces. For other types of audits, the auditors may need to get creative when breaking apart the risk categories. There is an audit risk calculation that the auditor then applies to each piece: Audit Risk = (Detection Risk) x (Inherent Risk) x (Control Risk). This formula determines the likelihood of inaccurate findings as well as undetected material misstatements. The only portion of this formula that the auditor can control is the detection risk.

Confirm Audit Objectives: At this point, the auditor has already assessed the risks and they can confirm what the audit objective(s) are. For example, in the case of a financial audit, the auditor can add specific objectives (sub-objectives), such as a review of the cash receipts.

Choose Audit Method: From the audit objectives, the methods for making conclusive determinations should flow naturally. The auditor will link each objective to a methodology so that there is strong evidence to back up their findings. Examples of methodologies include sampling, observations, interviews, and fluctuation analyses.

Link the Method to Cost: Once the auditor has decided on the methods, the auditor will budget out the cost so that the business has an idea of the overall cost for the audit.

Confirm the Audit Plan: Your auditor’s last step prior to their fieldwork is to confirm their plan with your business. Once your business confirms the plan and is comfortable with the number of hours that correlate to the methodology and costs, the on-site process can start.

The second main phase of your audit is the fieldwork. This is when your auditor or audit team is on-site at your office. They start by formalizing the audit program with your workforce, laying out their plan, and being introduced to staff members who will assist them by gathering and explaining documentation and processes. The following are examples of steps that your auditor may perform during your audit (the order depends on your auditor’s plan and necessity):

- Review the information systems

- Look at record-keeping policies

- Review the accounting system

- Review internal controls policies

- Compare the internal records

- Review the tax returns

- Perform tests of controls and the substantive test

Your auditor documents the results of each of these activities in their working papers. After they have completed their onsite reviews and tests, the auditor perform a comprehensive review of the working papers. Now, they can move to the reporting phase of the process. This last phase of reporting is when your auditor gets to write up their findings on your company. They may come back and confer with you or staff members prior to concluding and finalizing their report. This report gives you their conclusion on how your company adheres to accounting standards or the agreed-upon benchmarks.

What Is a Financial Auditor and What Is Their Report?

Equally important in this whole process is your auditor. The AICPA is very specific about the responsibilities and the functions of an independent auditor. Although there is some room for creativity in auditing practice, your auditor has a heavy responsibility not only to perform the audit based on their experience and best judgment, but also to act as a representative of their entire profession. They are required to perform the audit in accordance with standard auditing practices. It is your management’s responsibility to have sound accounting principles and internal controls, and to present them as such. However, if there are issues, it is your auditor’s responsibility to find and report them. Your auditor is bound by a code, and as such, that code may be enforced if they do not perform accordingly.

This can become a sticky problem when you have an auditor who is under pressure from the company that is funding their audit. On the one hand, the company being audited is paying the auditor for their needed service, and the auditor needs to support their own business. On the other hand, the company under audit may exert pressure by not hiring a particular auditor or firm or by withholding auditing fees in the case of an unfavorable outcome. Even subtle disfavor can harm the auditor personally. A scenario such as this can become an ethical dilemma for an auditor because as gatekeepers, they have a substantial responsibility. Experts suggest better incentive systems and policy reform for auditors overall, especially those faced with economic ethical dilemmas. It does save a company money when they retain the same auditing services annually. Although an audit takes a set amount of time, an auditor may become familiar with a company so that they can save time during the overall process.

The independent auditing service requirement, as enforced by the SEC, is that the auditor has no conflict of interest with the companies they audit. Additionally, they must not be in the position where they are auditing their own work, may become employed (separately) by the firm they audit, or where they will become an advocate for the company. They may not provide additional services, such as bookkeeping, financial information system design or implementation, actuarial services, brokering services, legal services, or valuation services. If a company seeks to hire a former employee to perform an audit, that auditor must refrain from doing so for a one-year period following his initial employment with said company. The audit committee must also assess any direct or material relationships the auditor has with the company in order to determine if those relationships conflict with independence.

In order to be an auditor, there are academic, professional, and personal requirements. The minimum educational requirement is a bachelor’s degree, but many employers prefer a master’s degree with a focus on finance or accounting. In order to audit public companies, an auditor must have the Certified Public Accountant’s (CPA) credential. They must stay current with the principles, theory, practice, and laws in accounting. They should also have integrity and tact when dealing with companies and a methodical practice. Many companies list personality traits, such as assertiveness and punctuality, that they want their auditors to possess. Nevertheless, selecting an auditor is ultimately about deciding whether you can entrust someone with the responsibility to perform their job and maintain your confidentiality. You must be able to rely on this person. The job descriptions for auditors are often interchangeable with those for accountants. Still, auditors perform more detailed work when it comes to finding fraud or errors in financial documentation.

In a job description, a financial auditor evaluates companies’ financial statements, documentation, accounting entries, and data. They may gather information from the company’s reporting systems, balance sheets, tax returns, control systems, income documents, invoices, billing procedures, and account balances. Then they conduct a comprehensive review of all this information in a fair, accurate manner to ensure there are no major errors or fraud. They must deal with different levels of management throughout different departments in pursuing data and information. They do this in order to gain an understanding of how the business operates, as well as of the company’s purpose and its reporting systems.

The national average salary for a financial auditor in 2017 was about $60,000. Different locations and firms adjust this figure, however, based on education, experience, expertise, and clientele. There are several types of auditors: These include internal auditors, government auditors, and independent auditors. Internal auditors and government auditors work in house. They can foresee and head off an organization’s major problems early. Internal auditors may not conduct independent audits, but they are valuable because of their capacity to advise on regular activities and systems. Government auditors are specific to federal or state agencies. Federal auditors work for the U.S. GAO and report to Congress.

An audit report is the final document that wraps up the audit. It is your written auditor opinion prepared in the standard format delineated by GAAS. Auditors write reports for users of the company’s financial statements. If your company is public, you include these reports when filing with the SEC.

How to Read and Understand a Financial Audit Report?

An audit report gives you an independent opinion on your company’s financial statements, and can help you make better economic decisions. Even though the report’s findings are based on persuasive (rather than conclusive) evidence, they still give you a fair estimate of a company’s financial position. In a financial audit by a CPA, the findings can be one of the following: an unqualified approval, a qualified approval, a disclaimer of opinion, or an adverse finding. The best result is an unqualified approval. The worst result is an adverse finding. Below, you’ll find descriptions of the four types of findings:

Unqualified Approval: This is essentially a clean bill of health for a company. It means that the auditor detected no internal control breakdowns during the audit.

Qualified Approval: This finding indicates that your auditor has encountered one of two scenarios: a single deviation from GAAP or scope limitation. The single deviation is one that breaks one of the GAAP rules. An example of a scope limitation is when your auditor cannot perform a test due to a dysfunctional system. Your auditor will explain the reasons for this type of qualification. In the case of a qualified approval, it is up to the reader of the report to decide if the identified problem affects the usefulness of the financial statements.

Disclaimer of Opinion: This type of audit report occurs when your auditor does not lay down any sort of opinion about the financial position of your company. Your CPA will state that they cannot provide an audit-related opinion or statement because of the limitation of the examinations they conducted.

Adverse Finding: An auditor issues this opinion when they determine that a company’s financial statements are materially misstated, should not be relied upon, and do not conform to GAAP when considered as a whole. This type of finding is a red flag for investors and can negatively affect business stock prices. The SEC does not allow publicly held businesses to trade their securities when auditors deliver adverse opinions.

Experts in reading audit reports recommend paying special attention to the introductory paragraphs, especially those concerned with management and auditor responsibilities, scope, and opinion. If you read and become familiar with audit reports, you will see that although each company is different, the reports are homogeneous and provide an excellent way to learn about a company.

How to Prepare for a Financial Audit?

It is normal to be nervous about an impending company audit. They be expensive and make you unsure about what your auditor will find. However, if you plan ahead of time, you can save money and assure that your auditor’s findings are only helpful.

As you’ve read in earlier sections of this guide, your auditor is looking for inconsistencies that could lead to financial inaccuracies. In their arsenal, your auditor has many different types of analytic procedures, though if they do not understand something, they will investigate and ask you or your staff questions. They will also ask for supporting documents to make sure you have recorded your financial information accurately. They will review your operational procedures and may review your information security to ensure that the data they are seeing is reliable.

To keep hours and costs down, there are steps you can take, including the following:

Implement Good Practices Year Round: If you put good processes in place, you can save time and money. Reconcile your information on a monthly or quarterly basis so errors do not compound. Regularly document your expenses and revenue during the year, and designate a place to store them so you do not have to struggle to find things.

Review Your Own Financial Information: Experts recommend reviewing your own financial information. This may be difficult if your company is very large, but if you are a business owner, your financials should make sense to you. If they do not, your auditors may also struggle to understand them, which adds more time to their investigation. Further, if you understand your situation, you are able to explain it to your auditor upfront.

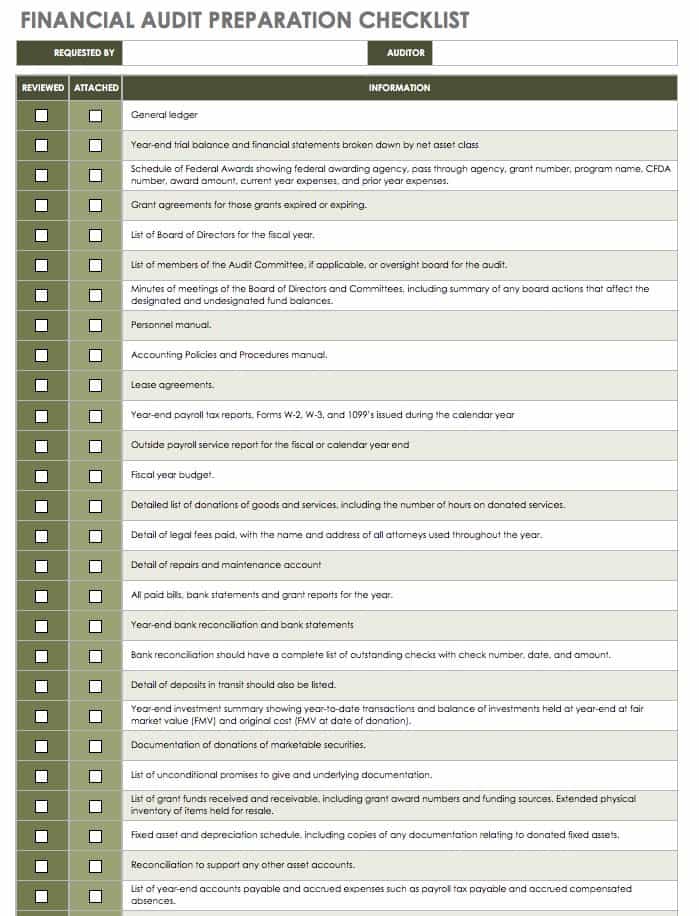

Get Your Paperwork Together: During the preparation phase of your audit, your auditor will request a list of documents and schedules. You or your accountant should be able to generate or gather this documentation. It is best to turn in this information by the auditor’s deadline, so they do not have to spend extra time and money tracking it down. Prior to sending information to your auditor, ask them what type of file they prefer to work with. Find a free checklist here that can get you started.

For more information on this visit TAXAJ

Related Articles

What is Statutory Audit & for whom is it Applicable?

Statutory Audit Meaning Statutory audit, also known as financial audit, is one of the main types of audit which is to be done as per the statutes applicable to the entity and its primary purpose is to gather all relevant information so that the ...Company Tax Return Audit In India

Tax Audit In India Section 44AB specifies that certain categories of individuals or businesses require tax audits by a chartered accountant in order to ensure compliance with the laws and to keep fraudulent tax practices in check. What is the ...Charitable Trust Audits in Bangalore

A certified chartered accountant must audit the organisation’s books if the total income of a charity trust or NGO exceeds the amount that makes it tax-exempt, according to Section 12A(1)(b) of the Income Tax Act of 1961. The income tax department ...What is forensic audit and how are they done?

Contrary to the name, a forensic audit has got nothing to do with forensic sciences, or criminology for that matter. A forensic audit, also known as forensic accounting, refers to the application of accounting methods for detection and gathering ...Tax Audit Services in Bangalore

Introduction Tax Audit Services in Bangalore provide essential financial oversight for businesses and individuals, ensuring compliance with the intricate web of tax laws and regulations. Operating in the vibrant IT hub of India, these services are ...